Collingwood Notables Database

Elizabeth Wilhelmina Skiddy

c. 1827-1911

Matron

Elizabeth Skiddy was matron of Dr John Singleton’s Retreat for Friendless and Fallen Women in Islington Street, Collingwood for an impressive stretch of 25 years. Here girls and women could stay for up to three months and were taught washing, ironing, housework, needlework and other household tasks, to give them skills for employment. The live-in matron or sub-matron was expected to be with the women continually.

In 1871 Dr John Singleton opened the Temporary Home for Friendless and Fallen Women, sponsored initially by the Society for the Prevention of Immorality. For many women in 19th century Australia, with no government pensions or other support, often far from family and friends, or rejected by their very families, the philanthropy of benefactors such as Singleton must have been a godsend. The fate of many such women might be prostitution, destitution, alcoholism, gaol under the vagrancy laws, or suicide. While Singleton was much given to proselytising and preaching the evils of drink, he was a genuine and caring philanthropist. His experience and understanding of the difficult position faced by many poor women in the colony was generally at odds with the severe approach often taken by other doctors and the police. While he saw the demoralising influence of low public houses as a factor in degraded lives, he placed more emphasis on the lack of cheap respectable lodging houses for women. And he did not place all the blame for ‘immorality’ on women.

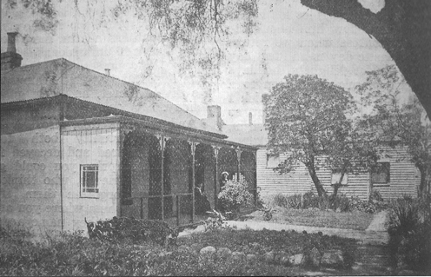

After a brief period in Condell Street, Fitzroy, just off Smith Street, Singleton purchased in 1874 a pair of two storey houses in Oxford Street, Collingwood (later numbered 43-45). At this time the matron was Sophia Lovely, a widow who had been running a private school in Smith Street, Collingwood. The final location of the Home was 32 Islington Street, Collingwood, where by February 1878 Singleton had obtained a six-roomed detached stone property set in a garden of about three-quarters of an acre. The house, known as Campbelltown Cottage, had been the residence of coach-builder John Ferguson.

Between 1871 and 1879, a total of 1066 women had been received as inmates. Of these, 845 had been found employment, become reconciled and restored to their families or friends, married to their seducers, or sent to other institutions. The remaining 216 left voluntarily, in the optimistic words of Singleton ‘many with apparently sincere intention of seeking their families, or some honest means of support’. Usually about a third of the women were friendless as opposed to fallen, short of funds and support because they had arrived from other places or lost their employment. Some friendless women were rescued from intended suicide, or from being sent to gaol under the vagrant law, or ‘proffered temptations to an immoral life’.

Christian ladies from the Melbourne City Mission visited back lanes in the city, left leaflets at dwellings and brothels or met women at the city watchhouse and the gaol. The home’s main income came from donations, with a lesser amount from a government grant, and a fifth or less from the laundry service and needlework carried out on the premises. Costs included annual salaries in 1879 of £37 16s 8d for the matron and £25 for the sub-matron. Inmates were encouraged to look on the institution as a real home, where they could be happy knowing, loving, and obeying the Saviour. Typically, numbers in the retreat at any one time were between seventeen and twenty, including several children.

Elizabeth Skiddy was appointed matron at Islington Street around 1885 after arriving in Melbourne, from New Zealand, where she had lived for six years. An Irishwoman, she was born Elizabeth Nicoll in Cork, where her father was a tobacco manufacturer. She married William Arthur Skiddy in 1848, bore five children, and was widowed in 1874.

While Singleton wrote endless reports and letters which emphasised the positive results of the enterprise, and attracted much fund-raising benevolence, the council and neighbours were often less charitable in their views. In 1886 Singleton had been desperately searching for a site to erect a night shelter for women and children, and had finally settled on building a timber dormitory in the grounds of the Home. At this point four members of the local Collingwood Board of Health accompanied by the mayor, the city surveyor, the town clerk, and the inspector of nuisances made an unexpected visit, which was reported in The Australasian:

The premises were reported to be in a very dirty and dilapidated state. The yard was strewn with refuse, there was a pile of rubbish against the neighbouring dwelling, and a pool of stagnant water under the dormitory. One of the front rooms was in a very untidy state, and the vicinity of the kitchen was thickly strewn with vegetables and stores. The members of the board considered the buildings and yard to be in a very unsatisfactory condition, and the matron was directed to have the place cleaned up, and the rubbish removed. The town clerk was sent … to urge … prohibition by the Central Board of Health of the use of the addition … which has just been completed. The board is strongly averse to the building being opened, and the opposition to a permit being granted is all the stronger owing to the state in which the other portion of the premises was found when the visit was made.

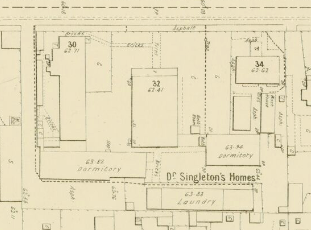

Not long before this, Mr Stanesby, a resident of Islington Street, had complained bitterly of ‘the disgusting scenes and language with which the street was polluted’, not to mention robberies. (See Stanesby: a moral and social cesspit.) In 1891 an application for exemption from rates was rejected by Council. Despite the agitations, the site eventually developed as a complex providing a night shelter for women and their children, and homes for widows, in addition to the Retreat. The 1899 MMBW detail plan (link below) shows the various houses, dormitories, a laundry and a wash house. The night shelter provided a place to sleep, and breakfast for homeless women and children, who had to leave after breakfast. In one month alone in 1894, 1026 people slept at the shelter, including 55 children.

It is hard to believe that an article in the Mount Alexander Mail, 10 January 1891, page 3, is referring to the same place. It describes a visit by a journalist to interview a Mrs Smith, resident of Dr Singleton’s Home. (This probably refers to the home for widows). She was believed to have been the first white woman to have resided in the colony of Port Phillip.

The garden in front was in full bearing, and rose trees shot out their buds and blooms. The air was laden with the most delicious perfumes, and surrounding all there was a lovely feeling of peace and quiet. What a lovely spot for old age to become older in! we thought as we accompanied the extremely pleasant matron along the vine-embowered walk to the house.

The presence of a sympathetic matron in the retreat would have been a major factor in the success of the enterprise. Despite her central role at the home, we know very little about Mrs Skiddy. This is fairly typical of much of women’s quiet work in the background, while Singleton himself was very well-known indeed and featured regularly in newspapers and other publicity. There are a few references to an unnamed but pleasant matron, as in the paragraph above; matrons (named) also feature in newspaper reports as witnesses in court cases such as wife desertion or infanticide.

In the 1890s Mrs Skiddy’s youngest child, Margaret, known as Madge, joined her mother at the Retreat as undermatron. She had been employed as a ship stewardess, sailing back and forth between New Zealand and Australian ports between 1884 and 1892. Mother and daughter worked together until 1911 when Elizabeth, by now 84, died after three weeks of illness following a stroke. Madge appears to have left not long after.

Singleton died 30 September 1891. In 1924 the Home in Islington Street was handed over by the Misses Singleton to the Melbourne City Mission to use the buildings as a home for middle aged or elderly women of limited means. In 1928-29 Singleton Lodge, a large red brick structure around a central courtyard garden, was built, and functioned until the late twentieth century. Singleton Lodge was demolished in 2002-2003 and in 2005 private units were built on the site.

Buildings 1899 detail plan

32 Islington St with timber night shelter in background

Life Summary

| Birth Date | Birth Place |

|---|---|

| c. 1827 | Cork, Ireland |

| Spouse Name | Date of Marriage | Children |

|---|---|---|

| William Arthur Skiddy, c. 1816-1874 | 1848 | William Arthur, William Henry, Robert William, May, Madge Adelaide c. 1860- 12 February 1921 |

| Home Street | Home City | Status of Building |

|---|---|---|

| Islington Street | Collingwood | Demolished |

| Work Street | Work City | Status of Building |

|---|---|---|

| Islington Street | Collingwood | Demolished |

| Church | Lodge |

|---|---|

| Anglican |

| Death Date | Death Place | Cemetery |

|---|---|---|

| 10 January 1911 | Collingwood | Boroondara |

Leader; The Age; The Argus; The Australasian; Bendigo Advertiser; Mercury; Mount Alexander Mail; Ovens and Murray Advertiser; Bendigo Advertiser; The Register (Adelaide); The Church of England Messenger; Hamilton Spectator; MMBW Detail Plan 1210; Otzen, Dr John Singleton, 1808-1891: Christian, doctor, philanthropist; Cummings, Bitter roots, sweet fruit; Ninth Annual Report of the Temporary Home for Friendless & Fallen Women at 32 Islington Street, Collingwood, for the year ending 31st December, 1879; Illustrated Australian News 1 June 1891 page 1.

Trove Lists: “Elizabeth Skiddy” “Home for Friendless Women”